monarch butterfly migration

“The monarch migration is truly a wonder.”

“... Here, you have a fragile insect weighing a half a gram, with a tiny brain, that comes out of Mexico in the spring, migrates up to the breeding areas where it has several generations, then migrates back again to an area that the year’s last generation has never been to. There are lessons for life in this butterfly and we need to protect it. If we don’t, we’re pretty lousy stewards of this planet and it bodes poorly for our future.”

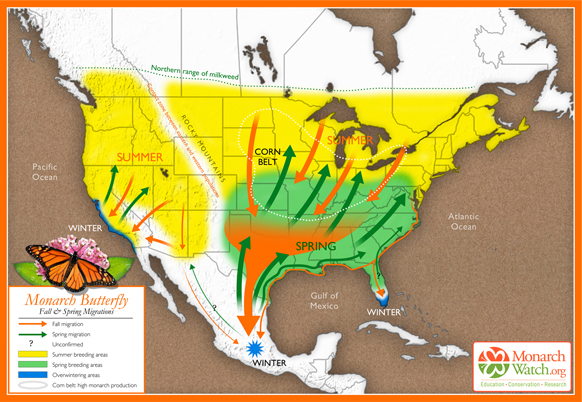

Orange is notes the fall migration, green is the spring migration, and yellow is the monarch's summer range. The overwintering areas are noted in blue. Based on original map design created by Paul Mirocha (paulmirocha.com) for Monarch Watch.

Monarch butterflies are known for their fantastic migration which is unlike any other butterfly in the world. They travel up to three thousand miles and are the only butterflies to make such a long, two-way migration every year. They somehow navigate to the same winter colonies, and often to the exact same trees, as the migrating monarchs before them.

There are three populations of monarch butterflies in North America—a large one east of the Rocky Mountains, a smaller one to the west, and another one is southern Florida where milkweed grows all year around. The Florida population is the only one which doesn't migrate. The monarchs east of the Rocky Mountains migrate to colonies high in the mountains of central Mexico. The monarchs west of the Rockies migrate to various locations on along the coast of central California. Populations of monarch butterflies in Costa Rica and Australia have also been found to make long winter migrations, but nothing compares to the North American monarch.

This map shows the migration patterns of the two populations of Monarchs, living on both sides of the Rocky Mountains. From their winter location the migrants begin to head back north in late February and early March (green). They lay eggs and the butterflies we see up in the midwest by early summer are almost always their babies. The yellow part of the map shows their summer range and the orange shows the journey back to Mexico in the fall.

In late summer, when the days are getting shorter and cooler, the last (4th) generation of monarchs for the year is born. This generation is unique: instead of living 4-6 weeks, breeding and laying hundreds of eggs, they can live up to eight months and migrate to and from the overwintering sites in Mexico. Those that migrate emerge from their chrysalis in a state of "reproductive diapause," which means that their reproductive organs remain in an immature state. Instead of mating and laying eggs, they spend their time drinking nectar and clustering together in nighttime roosts in preparation for their long journey south. Most of the monarchs will remain in diapause until the following spring, when they begin to mate in the overwintering colonies.

During September, October, and early November, migratory adults fly to overwintering sites in central Mexico, where they remain from November to March. Their migration is estimated to take two months.

As they migrate they accumulate fat when they stop to nectar along the way. This fat is stored in the abdomen and is a critical element of their survival for the winter. Most monarchs arrive in the colonies weighing more than when they started their long journey to get there, which is critical for their survival through the winter. This fat not only fueled their flight of one to three thousand miles, but must last until the next spring when they begin the flight back north.

Depending upon the temperature, it takes approximately one month for a monarch to complete its metamorphosis from egg to adult. Beginning with the first generation butterflies in the spring (babies of the returning migrants), there are four generations throughout the summer. (If the summer is cool there may only be three generations and if the summer is hot there may be five.) Below is my understanding of how this works:

generations of butterflies

Born late summer/early fall throughout eastern North America - they live up to eight months and migrate to Mexico for the winter. In early spring they breed and begin to migrate north, laying eggs in northern Mexico and the southern United States.

- 1st generation: (children of the migrants) - born early spring in northern Mexico and the southern U.S. - they live 4-6 weeks and will continue to migrate north.

- 2nd generation: (grandchildren of the migrants) -born early summer throughout the eastern U.S. - they live 4-6 weeks and some will continue to migrate north into Canada.

- 3rd generation: (great-grandchildren of the migrants) - born mid-summer throughout eastern North America - they live 4-6 weeks.

- 4th generation/Migrants: (great-great-grandchildren of the migrants) - born late summer/early fall throughout eastern North America - they live up to eight months and migrate to Mexico. It will take approximately two months for them to migrate and they'll roost in the same colonies, and sometimes the exact same trees, as their great-great-grandparents who migrated before them.

why do monarchs migrate?

Monarchs migrate because they can't survive freezing temperatures in any stage of their metamorphosis. Most other butterflies and moths overwinter in the chrysalis stage in locations where it freezes. Some go through the winter as eggs, caterpillars, and butterflies. The all have some sort of anti-freeze that keeps them alive, much like frogs and turtles and other creatures who survive the winter in freezing temps. In the winter, while the Monarchs are hanging out in Mexico, south Florida, or the southern California, look up into the barren trees and it's quite likely you're looking at butterflies and moths in some stage of metamorphosis, waiting for spring. Some hibernating butterflies choose to stay behind dead bark that's separated from trees. Some caterpillars curl up in the dead leaves for the winter.

where to they go?

With many thanks to Dr. Fred Urquhart, we know that the majority of the eastern monarch population migrates to overwintering colonies in Mexico. Dr. Urquhart (d. 2002) was an internationally renowned expert in the migration patterns of the monarch butterfly, as well an extensive researcher of their life cycle. In his life-long quest to discover where monarchs go for the winter, Dr. Urquhart began tagging monarchs in 1937 by marking their wings. In 1952 he and his wife Norah involved thousands of citizens in their tagging program, leading to the discovery of the monarch's overwintering colonies in 1975, near the city of Angangueo, Mexico, in the Sierra Madre mountains. It's approximately 4-5 hrs driving time (118 mi/187 km) west of Mexico City. Today thousands of people participate in a great monarch tagging program conducted by Monarch Watch. (Read Dr. Urquhart's article "Found at Last; The Monarch's Winter Home" about this discovery, originally published in National Geographic magazine in August 1976.)

Now available on Netflix, Flight of the Butterflies is an amazing and beautiful IMAX film about Dr. & Norah Urquhart's 40 years of work to discover the monarch migration from Canada to Mexico. Millions of monarchs were filmed in the colonies in Mexico, creating sights and sounds you'll never forget. Please watch it when you get a chance!

Twelve Over-wintering Colonies in Mexico

Monarchs cluster by the millions in twelve over-wintering monarch colonies in Mexico, all within an area that's only 73 miles wide. They form colonies at elevations above 10,000 feet on the southwest slopes in Oyamel fir forests, where the humidity and temperatures are exactly what they need to be able to survive the winter. And even throughout the winter, as the humidity changes, the colonies often move to different locations on the mountain. These very rare areas are located on just a dozen mountaintops in central Mexico and are shrinking as illegal logging continues to take place and destroys their delicate habitat.

Not only does the total number of monarchs fluctuate from year to year, but within the over-wintering colonies the percentage of the population between them can vary greatly as well. The three major colonies - El Rosario, Cerro Pelon, and Sierra Chincua - are made up of the vast majority of the migrants every year, accounting for some 68 - 78% of all the migrants in 2009-2010. Some over-wintering sites don't see any migrants at all one year but may have some the next.

How do they get there?

Another unsolved mystery is how Monarchs find the overwintering sites each year. Most of the butterflies in this final generation begin their lives in the northern US or southern Canada, and then migrate thousands of miles to mountaintops that neither they nor their parents or grandparents have ever seen before. They can fly about 80 miles a day using air currents and soaring like birds, which enables them to fly more efficiently. Somehow they know the way, possibly by using the sun and the earth's magnetic field, or by an internal compass. In April 2016, researchers think they cracked the secrets of the mystery of how they find their way. Read "Scientists crack secrets of the monarch butterfly's internal compass."

Google Maps – it's 1,998 miles from Indianapolis (39:46:35N 86:08:46W) to Angangueo, Mexico. The peak migration dates for Indianapolis are Sept. 14-26 with the midpoint being Sept. 22.

Google Maps - 116 miles (186 km) from Mexico City to Angangueo, Mexico

Journey North - the best website to track the fall and spring migrations!

Monarch Butterfly Migration Threatened By Habitat Destruction

For years now the number of migrating monarchs has been on a serious decline due to the destruction of habitat in all of North America, not just in Mexico. Between the illegal logging in Mexico and the destruction of milkweed habitats in the U.S., along with the use of pesticides, the monarchs are facing huge challenges to survive. Sadly, the vast majority of their problems are man-made.

"The monarchs’ numbers have been cut in half in recent years, some researchers say, and they put much of the blame on hardier farm crops in the Midwest. Monarchs lay their eggs on milkweed plants. But thanks to genetically modified corn and soybeans that withstand herbicides, farmers can now wipe out milkweed from their land without damaging their crops. That means monarchs can no longer find milkweed on 100 million acres of farmland. Combine that loss with deforestation in Mexico, where monarchs winter, and you have a vanishing species.

'It’s clear we’ve lost an awful lot of habitat, mostly over the last 10 years,' said Orley 'Chip' Taylor, who leads Monarch Watch, based in Lawrence, Kan. 'The population has declined significantly.'

In Mexico and the United States, monarchs are losing habitat at the rate of about 6,000 acres a day, estimate Jim Lovett and Ann Ryan, Monarch Watch staffers. Monarch Watch says there are several ways to reduce the threat. The center encourages people to create microhabitats (Waystations, see below) with milkweed for monarch eggs and nectar plants for grown butterflies. The program has helped start 5,000 of these habitats. Monarch Watch also encourages people to plant milkweed all over, including roadsides." (Quoting from the article "Habitat loss imperils monarch butterflies.")

In the article "Habitat Destruction May Wipe Out Monarch Butterfly Migration, Researcher Says," it's clear the need to reverse what's happening is urgent:

"Intense deforestation in Mexico could ruin one of North America's most celebrated natural wonders — the mysterious 3,000-mile migration of the monarch butterfly. According to a University of Kansas researcher, the astonishing migration may collapse rapidly without urgent action to end devastation of the butterfly's vital sources of food and shelter.

'To lose something like this migration is to diminish all of us,' said Chip Taylor, KU professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. 'It's so truly spectacular, one of the awe-inspiring phenomena that nature presents to us. There is no way to describe the sight of 25 million monarchs per acre — or the sensation of standing in a snowstorm of orange as the butterflies cascade off the fir trees."

how can we help the monarchs?

Plant MILKWEED! It seems like a big answer to many of this butterfly's problems. Of course nothing is that simple. There are many issues with illegal logging in Mexico as well. Pictured here are two milkweeds growing in a field, Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), and the heart-shaped leaves of Sand Vine (Cynanchum laeve).

Another thing that will help is to create a Monarch Waystation in your yard and wherever possible. Waystations provide milkweed plants for the larva and nectar-producing flowers to fuel the adult butterflies. In addition, they provide a pesticide-free, protected place where the monarchs can rest, feed, mate, and breed in peace. By creating the Waystation you will contribute to Monarch conservation, helping ensure the preservation of the species and its spectacular seasonal migration.